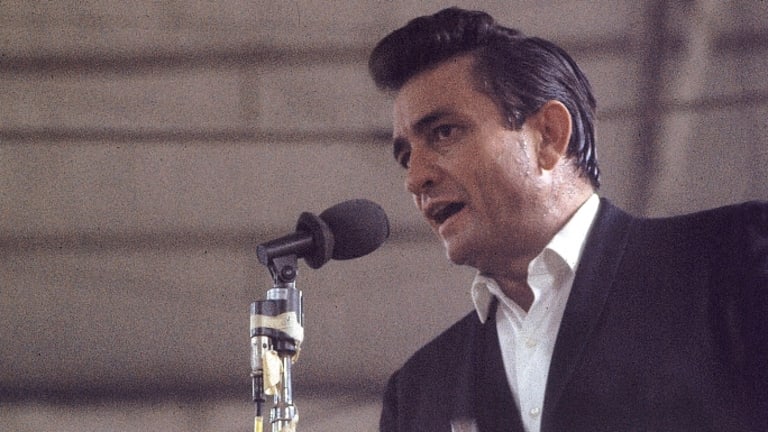

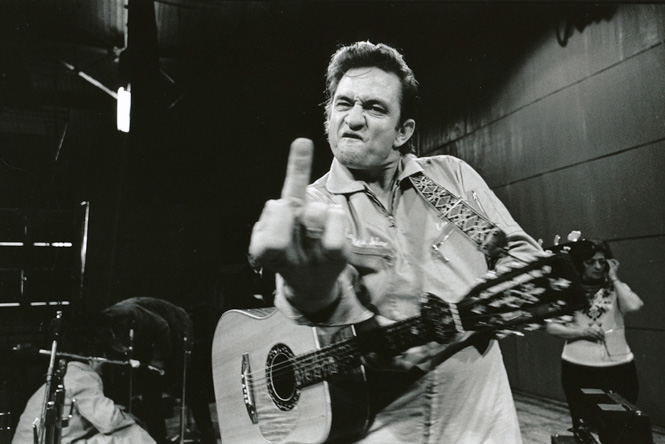

Wanted to have a little fun today. What better way to celebrate July 4th than with Willie Nelson and my next American Artist? The Willie Nelson set I watched on June 25th was probably the first real country act I’ve seen in concert, other than in street fairs in Nashville. Willie has done what few others have: appealed to a vast array of genres like Johnny Cash and Dolly Parton. The man is 92 and still going out there every night.

The couple in front of us took this picture.

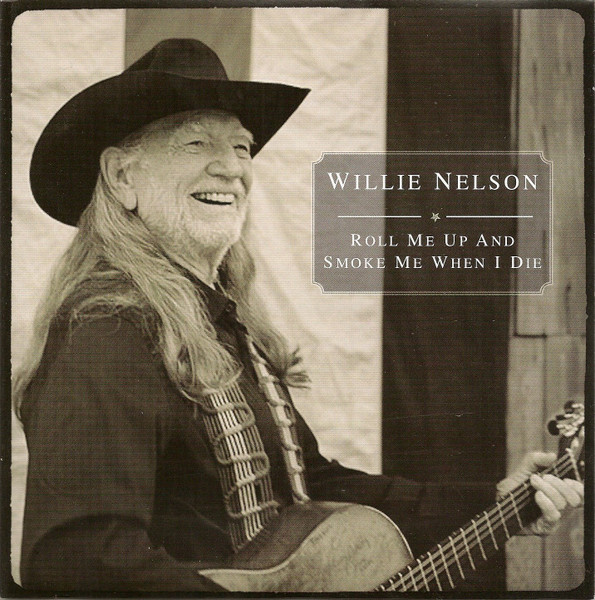

If there were a Mount Rushmore for country outlaws, Willie Nelson wouldn’t just be on it, he’d be carving the damn thing with a joint in one hand and Trigger (his guitar) slung over his back. And with this song, Willie laughs at his legend and turns it into a porch-sing-along for the afterlife.

Released in 2012 on his Heroes album, this track arrived with a puff of smoke, wrapped in that unmistakable red-headed goodness. It’s a song about death that somehow feels like a party. Leave it to Willie to make his own funeral plans sound like a tailgate party. Beneath the title and chorus is something far more poignant: a man looking mortality in the eye and saying, You’re not killing my vibe.

The lineup of guests: Snoop Dogg, Kris Kristofferson, and Jamey Johnson all pile in for the chorus like it’s some high-end dive bar jam session. The vibe is half gospel, half roadhouse. The songwriters are Willie Nelson, Buddy Cannon, Rich Alves, John Colgin, and Mike McQuerry.

Roll Me Up and Smoke Me When I Die

Roll me up and smoke me when I dieAnd if anyone don’t like it, just look ’em in the eyeI didn’t come here and I ain’t leaving, so don’t sit around and cryJust roll me up and smoke me when I die

Now you won’t see no sad and teary eyesWhen I get my wings and it’s my time to flyCall my friends and tell ’em there’s a party, come on byAnd just roll me up and smoke me when I die

Roll me up and smoke me when I dieAnd if anyone don’t like it, just look them in the eyeI didn’t come here and I ain’t leaving, so don’t sit around and cryBut just roll me up and smoke me when I die

And I’d go, I’ve been here long enoughSo sing and tell more jokes and dance stuffJust keep the music playing, that will be a good goodbyeRoll me up and smoke me when I die

Roll me up and smoke me when I dieAnd if anyone don’t like it, just look ’em in the eyeI didn’t come here and I ain’t leaving, so don’t sit around and cryJust roll me up and smoke me when I die

Hey, take me out and build a roaring fireRoll me in the flames for about an hourAnd take me out and twist me up and point me towards the skyAnd roll me up and smoke me when I die

Roll me up and smoke me when I dieAnd if anyone don’t like it, just look ’em in the eyeI didn’t come here and I ain’t leaving, so don’t sit around and cryJust roll me up and smoke me when I die

Just roll me up and smoke me when I die

…