The tone of this track is ominous. What a powerful statement The Stones were making in this song. With me growing up in the late 70s and 80s I didn’t grasp what the song was getting across when I first heard it. We didn’t have the turmoil that was going on during the sixties happening at that time.

Now the tone…something about the sixties that is missing today is the low fi experimenting. Keith Richards started developing this song in late 1966 but had a hard time getting the sound he was after. The breakthrough came when he bought a Philips cassette recorder and realized he could get a dry, crisp sound by playing his acoustic guitar into it and overloading it. The only electric instrument on the entire song is the bass. The guitar you hear is coming from an old Philips cassette recorder.

Charlie Watts used a 1930s toy drum kit called a London Jazz Kit Set…it was something close to this…

The song was released in 1968 and was on Beggars Banquet. The song peaked at #48 in the Billboard 100, #21 in the UK, and #32 in Canada.

From Songfacts

This song deals with civil unrest in Europe and America in 1968. There were student riots in London and Paris, and protests in America over the Vietnam War. The specific event that led Mick Jagger to write the lyric was a demonstration at Grosvenor Square in London on March 17, 1968. Jagger (along with Vanessa Redgrave), joined an estimated 25,000 protesters in condemning the Vietnam War.

The demonstrators marched to the American embassy, where the protest turned violent. Mounted police charged the crowd, which responded by throwing rocks and smoke bombs. About 200 people were taken to the hospital and another 246 arrested. Jagger didn’t make it to the embassy: before the protest turned violent, he abandoned it, returning to his home in nearby Cheyne Walk. Jagger realized that his celebrity was a hindrance to the protest, as his presence distracted from the cause.

This was the first Stones song to make a powerful political statement, although with an air of resignation. Jagger opens the song declaring “the time is right for fighting in the street,” but goes on to sing, “But what can a poor boy do, ‘cept sing in a rock and roll band.”

This sense of hopelessness in the face of atrocity may be why the Rolling Stones became apolitical, focusing their efforts on songs about relationships and rock n’ roll. In the process, they became very rich and beloved by members of all political persuasion.

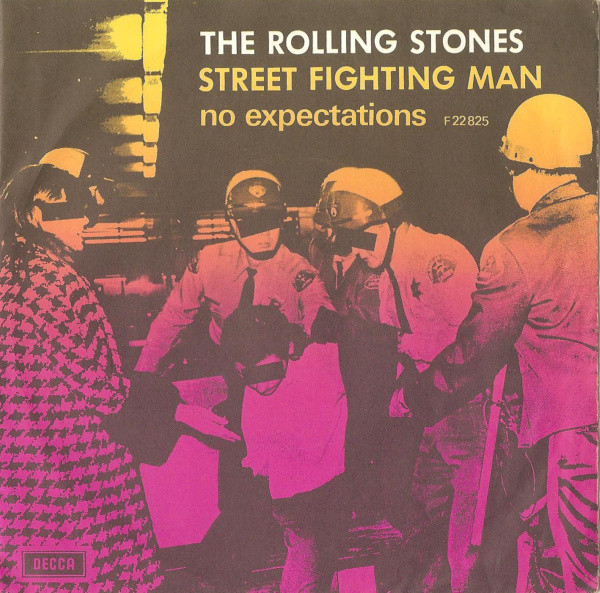

In the US, this was released as a single on August 31, 1968, just a few days after the Democratic National Convention, which took place August 26-29. The convention was marred by violence, as Chicago police clashed with protesters. When the song was released, every radio station in Chicago (and most in the rest of the country), refused to play it for fear that it would incite more violence. There was no official ban in America or Chicago, but stations knew it was in their best interest to shun the song, which accounts for its meager chart position of #48.

Mick Jagger later said: “The radio stations that banned the song told me that ‘Street Fighting Man’ was subversive. ‘Of course it’s subversive,’ we said. It’s stupid to think you can start a revolution with a record. I wish you could!”

The original title of this song was “Did Everybody Pay Their Dues?” It had completely different lyrics and therefore altogether a different and rather strange meaning, with Jagger singing about an Indian chief and his family. The music however was basically the same (slightly alternative mixes exist), but the lead guitar over the chorus was omitted on the final mix of “Street Fighting Man.” Fairly listenable versions have appeared on various bootlegs.

Keith Richards created a distinctive guitar sound on this track using a technique he also used on “Jumpin’ Jack Flash,” where his acoustic guitar was overdubbed several times. Said Richards: “‘Street Fighting Man’ was all acoustics. There’s no electric guitar parts in it. Even the high-end lead part was through a cassette player with no limiter. Just distortion. Just two acoustics, played right into the mike, and hit very hard. There’s a sitar in the back, too. That would give the effect of the high notes on the guitar. And Charlie was playing his little 1930s drummer’s practice kit. It was all sort of built into a little attaché case, so some drummer who was going to his gig on the train could open it up – with two little things about the size of small tambourines without the bells on them, and the skin was stretched over that. And he set up this little cymbal, and this little hi-hat would unfold. Charlie sat right in front of the microphone with it. I mean, this drum sound is massive. When you’re recording, the size of things has got nothing to do with it. It’s how you record them. Everything there was totally acoustic. The only electric instrument on there is the bass guitar, which I overdubbed afterwards. What I was after with all of those – Street Fighting Man, Jumping Jack Flash – was to get the drive and dryness of an acoustic guitar but still distort it. They were all attempts at that.”

Dave Mason did session work on this track. He played the shelani, an Indian reed instrument, which comes in near the end of the song. Mason went on to form the group Traffic, and has played guitar on albums by Jimi Hendrix, George Harrison, Paul McCartney and Fleetwood Mac.

Mick Jagger said of this song: “It was a very strange time in France. But not only in France but also in America, because of the Vietnam War and these endless disruptions…. I wrote a lot of the melody and all the words, and Keith and I sat around and made this wonderful track, with Dave Mason playing the shelani on it live. It’s a kind of Indian reed instrument a bit like a primitive clarinet. It comes in at the end of the tune. It has a very wailing, strange sound.”

This was recorded on an 8-track machine with one track devoted to the cassette recording Richards and Watts made together. Richards added more acoustic guitar on another track, Watts put some bass drum on another, and the rest were filled out by Jagger’s vocal and the other instruments: Jones on sitar and tamboura, Dave Mason’s shehnai, Nicky Hopkins on piano and Richards on bass because Bill Wyman wasn’t around. There is a great deal of stereo separation in the mix.

In the US, the single was originally released with a picture on the sleeve of police beating protesters in Los Angeles. The music was different on this version, with different vocals and more piano. This single was quickly pulled by the record company and is now a rare collectors item.

The studio recording, with acoustic guitars and sitar, is impossible to replicate live, but the group came up with an electric arrangement that packed plenty of punch when they performed it. The song remained a concert favorite throughout their run.

The Stones released this the same month The Beatles came out with “Revolution,” which was their first blatantly political song.

A number of sources claim that this song was inspired by the radicalism of a young student leader Tariq Ali, who was active in revolutionary socialist politics in Britain in the late ’60s. In an interview with the April 19, 2007 edition of the Galway Advertiser, Ali, who is now a writer and filmmaker, confirmed this. “Yes, its true. Jagger was/is an artist. He writes and sings what he wants.”

In the UK, this wasn’t released as a single until July 1971, but it still made a strong showing on the chart, reaching #21.

Rod Stewart covered this on his 1973 album Sing It Again Rod. Rage Against The Machine covered it on their 2000 album Renegades.

Mick Jagger said in 1995: “I’m not sure if it really has any resonance for the present day. I don’t really like it that much. I thought it was a very good thing at the time. There was all this violence going on. I mean, they almost toppled the government in France; De Gaulle went into this complete funk, as he had in the past, and he went and sort of locked himself in his house in the country. And so the government was almost inactive. And the French riot police were amazing. Yeah, it was a direct inspiration, because by contrast, London was very quiet.”

Engineer Eddie Kramer recalled to Uncut in a 2016 interview: “The beginning of Street Fighting Man? My recollection is that Jimmy Miller brought in a Wollensak – a cassette machine with one mic built in – stuck it on the floor, pressed ‘Record’ and the band just make a circle round it. And that was the basic track. Now, of course, Keith says it was his idea and his tape machine, but I don’t remember it that way.”

Keith Richards lists this among his favorite Rolling Stones tracks, and feels the message rings true. “When people feel that mad about the way they’re being run, you should go to the streets,” he said. “America wouldn’t be here if it wasn’t for people going to the streets.”

Street Fighting Man

Ev’rywhere I hear the sound

Of marching charging feet, boy

‘Cause summer’s here and the time is right

For fighting in the street, boy

Well now, what can a poor boy do

Except to sing for a rock n’ roll band?

‘Cause in sleepy London town

There’s just no place for a street fighting man, no

Hey think the time is right

For a palace revolution

But where I live the game

To play is compromise solution

Well now, what can a poor boy do

Except to sing for a rock n’ roll band?

‘Cause in sleepy London town

There’s just no place for a street fighting man, no. Get down.

Hey so my name is called Disturbance

I’ll shout and scream

I’ll kill the king, I’ll rail at all his servants

Well, what can a poor boy do

Except to sing for a rock n’ roll band?

‘Cause in sleepy London town

There’s just no place for a street fighting man, no

Get down